Niger J Paed 2014; 41 (4): 345 - 349

ORIGINAL

Akodu SO

Exclusive breastfeeding practices

Njokanma OF

Disu EA

among women attending a private

Anga AL

health facility in Lagos, Nigeria

Kehinde OA

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njp.v41i4,11

Accepted: 31th May 2014

Abstract

Background: Exclusive

sively breastfed (3.6%).

breast feeding (EBF) is an effec-

No

association was found between

Akodu SO

(

)

tive tool of child survival. While

breastfeeding pattern and variables

Njokanma OF, Disu EA, Anga AL

many

mothers understand the

such

as gender of infants, place of

Kehinde OA

importance of breast

feeding,

delivery, maternal age, type of

Department of Paediatrics

some circumstances may hinder

delivery and number of antenatal

Lagos State University Teaching

visits. On the contrary there was

Hospital, Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria

the practice.

Email: femiakodu@hotmail.com

Objective: To

determine the

pat-

an

association with following vari-

tern and factors influencing EBF

ables: birth order among mother

among women attending a private

siblings, prenatal and postnatal

health facility in Lagos, Nigeria.

feeding advice.

Methodology: One

hundred and

Conclusion: The

rate of

exclusive

twelve mothers with children aged

breast feeding among mothers for

twelve months or less were inter-

the recommended six months was

viewed through a questionnaire on

very low (3.6%). Antenatal and

their breastfeeding practices.

postnatal programmes that will

Results: At

the end

of second

encourage mothers to practice ex-

month, two-fifths of the babies

clusive breastfeeding should be

were still exclusively breastfed.

strengthened.

This dropped to one-fifth by the

end

of the fourth month. At the

Key words: Exclusive

breast feed-

end of six months, less than one-

ing, survival analysis, practice,

tenth of subjects were still exclu-

private hospital, mother

Introduction

the year 2003 2 .

According to the Nigerian Demographic

and Health Survey (NDHS), in 2008, 17% of children

Exclusive breastfeeding means that the infant receives

were exclusively breastfed for up-to four months, while

13% were exclusively breastfed up-to six months . This

2

only breast milk (either directly from the breast or ex-

pressed) and no other liquids or solids are given – not

data suggested a deteriorating situation; however, there

even water – with the exception of oral rehydration solu-

is

little or no information on the factors contributing to

tion, or drops/syrups of vitamins, minerals or medici-

this situation.

nes . The WHO recommends that infants should be ex-

1

clusively breastfed for the first six months of life to

The low proportion of women practicing EBF in most

achieve optimal growth, development and health.

2

developing countries has been attributed to various ma-

Thereafter, infants should receive nutritionally adequate

ternal and child factors including place of residence,

and

safe complementary foods, while continuing to

gender and age of the child, mother working outside

breastfeed for up to two years or more.

home, maternal age and educational level, access to

mass

media and economical status

9–11

Promotion of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) has been a

.

Against the back-

cornerstone of public health measures to promote child

ground that the relative importance of these and similar

survival for several decades . EBF is associated with

3,4

factors may differ from one environment to another, the

reduced risks of diarrhoea–and pneumonia–related in-

current

study sought to assess exclusive breastfeeding

fant morbidity and mortality both developed and devel-

patterns among women attending a private health facility

oping world settings

5–

8

.

in

Lagos, Nigeria. Although several local studies have

been carried on the pattern of breast feeding among

Based on the WHO Global data on Infant and Young-

mothers, to the knowledge of the authors no study had

Child Feeding in Nigeria, 22.3% of children were exclu-

recruited mothers attending private hospitals. The im-

sively breastfed for less than four months, while 17.2%

portance of conducting the study in a private healthcare

were exclusively breastfed for less than six months, in

facility stems from the fact that clients of such facilities

346

are

often employed outside the home and are of rela-

First, at any time, subjects who are censored have same

tively high socioeconomic class.

survival prospects as those who continue to be followed.

Second, survival probabilities are the same for subjects

recruited early and late in the study. Third, the event

happens at the time specified. Survival probabilities,

Methodology

standard error, hazard rate and median survival time

were obtained. Log rank test for comparison of group

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study carried out

was also applied to compare EBF experiences of groups.

over a five–month period from March through July 2013

among women who brought their children to the immu-

EBF indicator was expressed as a dichotomous variable

nization unit at Isalu Hospitals Limited. Isalu Hospitals

with category “1” for EBF and category “0” for non-

Limited

is a private health facility located in Ogba,

EBF. This variable was examined against a set of inde-

Ikeja. Ogba is about five kilometres west of Ikeja, the

pendent variables (maternal and child characteristics) in

capital city of Lagos State. It is a densely populated area

order to determine the prevalence of EBF and factors

with a mixture of housing for high and low income earn-

associated with the duration of EBF. Log rank tests were

ers.

used to assess the significance of factors associated with

EBF and those with p < 0.05 were considered signifi-

Written and verbal informed consent was obtained from

cant.

respondents who brought their children to immunization

unit after explaining the purpose of the study. The tar-

gets were mothers with children aged less than twelve

months. Eligible subjects who consented were recruited

Results

consecutively.

Characteristics of the study subjects

Women were interviewed through a study proforma

The

characteristics of recruited mothers and their chil-

which included general information, socio-demographic

dren

are shown in Table 1. A total of 112 eligible

status, number of births, and duration of exclusive

mother-infant pairs were recruited for the study. Major-

breastfeeding, The duration of exclusive breastfeeding

ity

of the recruited mothers were above 30 years of age,

(in

months) here refers to the period from the first breast

have

tertiary educational status, are working mothers

milk

feed to the introduction of semi-solid or liquid food

and

belong to the upper socioeconomic strata. The most

supplements along with breastfeeding. Social classifica-

prevalent age group of the children was 9 – 11 months.

tion

was done using the scheme proposed by Oyedeji

12

Male and female children were nearly equally repre-

and subjects were classified into five classes (I – V) in

sented in the sample. Of the total births, 91.1% took

decreasing order of privilege. Socio-economic index

place at a private owned facility. The proportion of de-

scores (1 to 5) were awarded to each subject, based on

livery by caesarean section was 34.8%.

the occupational and educational levels of parents.

Cumulative probabilities for exclusive breast feeding

Data

were entered and analyzed using the Statistical

(EBF)

Package for Social Science (SPSS) 18.0 version. Those

women who were continuing EBF on the date of inter-

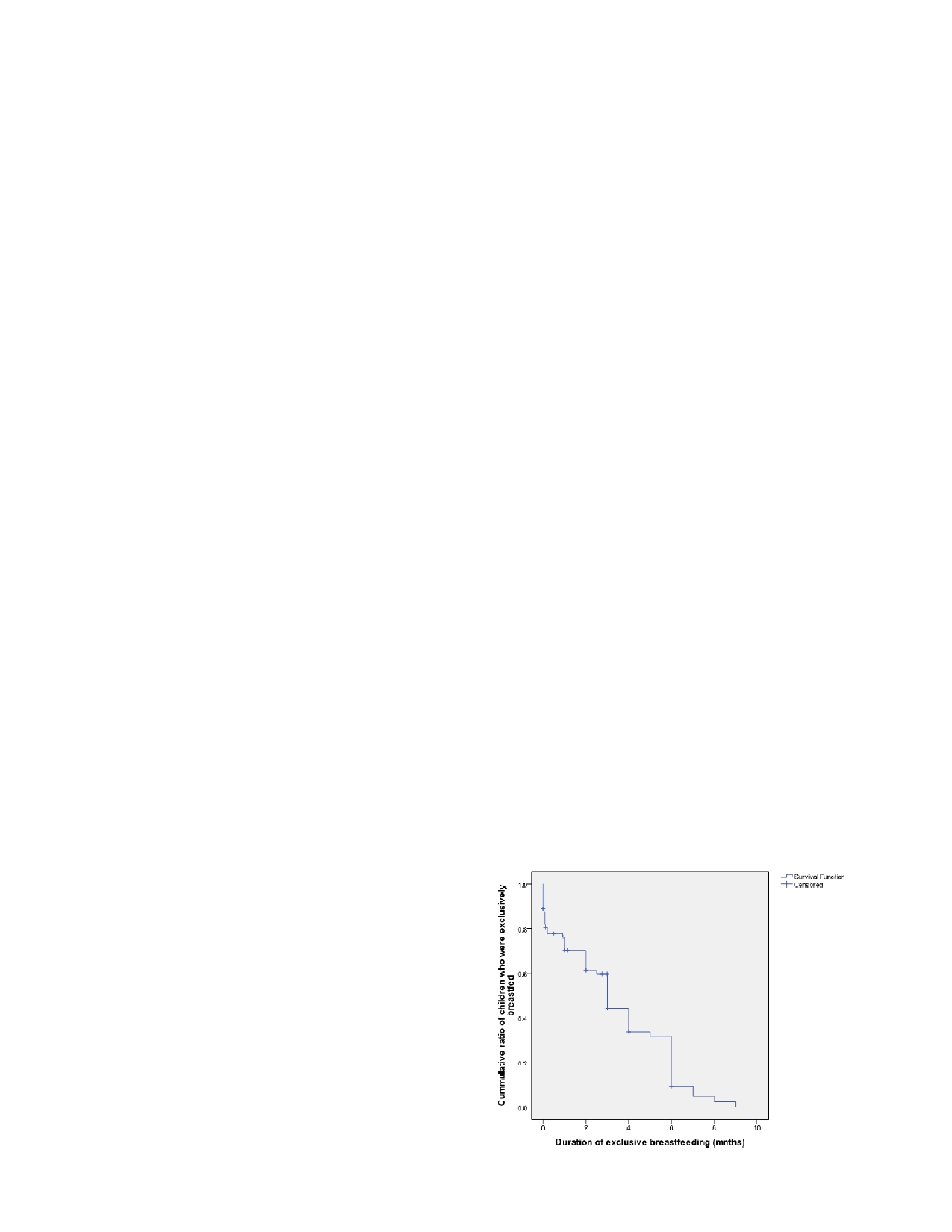

On

the basis of the life table technique, Figure 1 shows

view were considered censored cases and their duration

survival probability for duration of exclusive breastfeed-

of

EBF was recorded and treated as censored data, as it

ing

among study infants.

was

not known when they would discontinue EBF. They

contributed valuable information and were not to be

Fig 1: Survival

curve showing

survival probability for

duration

omitted from relevant aspects of the analysis. It would

of

exclusive breastfeeding

also

be wrong to treat the observed time at censoring as

exclusive breastfeeding termination time. A statistical

technique useful for such data is survival analysis. Life

table and the Kaplan Meier method was used to subdi-

13

vide

the period of observation into smaller time intervals

and

for each interval, all who had been observed at least

that

long were used to calculate the probability of a ter-

minal event occurring in that interval. The life table

technique allows us to consider children who were still

being breastfed at the time of interview of mothers, and

also

to know the proportion of children that remain be-

ing

breastfed by the end of each month of their life. So,

it

allows a longitudinal approach to the cross sectional

data

collected. The probabilities estimated from each of

the

intervals were then used to estimate the overall prob-

ability of the event occurring at different time points.

There were three assumptions for this methodology.

347

Table 1: Characteristics

of mothers

and children

Table 2: Cumulative

probabilities for

exclusive breast

feeding

Characteristic

N

%

using survival analysis

Gender of infant

Breast feeding

No

entering

No

of cumu-

No

of

Male

59

52.7

interval

the

interval

lative events

remaining

Female

53

47.3

(months)

cases

Age

of infant (months)

<3

40

35.7

0 –

1

112

22

65

3 –

5

13

11.6

1 –

2

65

28

45

6 –

8

4

3.6

2 –

3

45

38

27

9 –

11

46

41.1

3 –

4

27

44

18

No

response

9

8.0

4 –

5

18

45

17

Position of birth

5 –

6

17

57

4

1

46

41.1

>1

61

54.5

6 –

7

4

59

2

No

response

5

4.4

7 –

8

2

60

1

Place of delivery

8 -

9

1

61

0

Private hospital

102

91.1

Government hospital

10

8.9

Maternal age (years)

Factors associated with being exclusively breast fed

>30

73

65.2

21

– 30

39

34.8

Table 3 presents the survival analysis to investigate vari-

Mother’s education status

ables associated with being exclusively breastfed. The

Secondary

3

2.7

Tertiary

107

95.5

median duration for EBF was same for the female and

No

response

2

1.8

male babies (p = 0.757). The median duration of EBF

Father’s education status

was significantly longer among subjects of the second or

Secondary

1

0.9

higher birth order. The place of delivery, maternal age,

Tertiary

108

96.4

No

response

3

2.7

type of delivery and number of antenatal visits were not

Mother’s working status

associated with significant differences in median dura-

Housewife

2

1.8

tion of EBF (p > 0.05). On the contrary the report of

Working outside home

108

96.4

prenatal and postnatal feeding advice was associated

No

response

2

1.8

Socioeconomic status

with significantly longer median duration of EBF com-

Upper strata

106

94.6

pared with mother who reported no prenatal and postna-

Others

5

4.5

tal feeding advice (p < 0.05).

No

response

1

0.9

Type of delivery

Table 3: Survival

analysis of

factors associated

with exclu-

SVD

73

65.2

sively breastfeeding

C/S

39

34.8

Received prenatal feeding advice

Characteristic

No

of

No

of

Median duration of

Log

termi-

cen-

EBF

(months)

rank test

Yes

97

86.6

nal

sored

SE

(95% CI)

for

No

14

12.5

events

cases

com-

No

response

1

0.9

parison

of

group

Received postnatal feeding advice

Gender

0.757

Yes

71

63.4

Male

35

24

4.0

No

30

26.8

0.39 (3.25 – 4.76)

No

response

11

9.8

Female

26

27

4.0

0.75 (2.53 – 5.47)

Position of birth

1

26

20

3.0

0.012

Out of 112 women surveyed, 61 (54.5%) reported termi-

0.24 (2.53 – 3.47)

>1

33

28

6.0

nation of EBF on or before survey date (terminal event).

0.30 (5.41 – 6.60)

2.0

The remaining 51 (45.5%) cases were censored cases as

No

response

2

3

Place of delivery

0.510

they were still continuing EBF on the survey date. The

Private hospital

56

46

4.0

0.54 (2.94 – 5.06)

overall exclusive breastfeeding rate was 42.9 percent.

Government hospital

5

5

3.0

Maternal age (years)

0.22 (2.57 – 3.43)

Table 2 show the cumulative probabilities for EBF using

>30

survival analysis. In relation to exclusive breastfeeding,

42

31

3.0

0.671

21

– 30

0.41 (2.20 – 3.80)

it

was observed that this was not a universal practice

Type of delivery

19

20

4.0

0.64 (2.75 – 5.25)

immediately after birth as 22 (19.7%) had formula feed

C/S

17

22

6.0

introduced. The maximum numbers of babies who

SVD

1.51 (3.05 – 8.96)

44

29

4.0

0.767

stopped EBF did so during first month of age interval,

Number of antenatal visits

0.43 (3.17 – 4.83)

1 –

3

4

3

4.0

which are 22 babies. By the end of second month, forty-

2.49 (0.00 – 8.89)

five of the recruited children were still exclusively

More than 3

55

46

4.0

0.38 (3.26 – 4.74)

breastfed, which further dropped to eighteen by the end

No

response

2

2

0.00

0.766

4.0

of

the fourth month. At the end of six months, four of

Received prenatal feeding advice

0.51 (3.01 – 4.99)

the recruited children were still exclusively breastfed.

Yes

51

46

1.0

0.44 (0.13 – 1.89)

The median length of exclusive breastfeeding (age in

No

9

5

2.0

which half of the children received only the mother’s

No

response

1

0

4.0

0.001

milk) was found to be three months (with 95% confi-

Received postnatal feeding

0.49 (3.05 – 4.95)

advice

3.0

dence interval 2.61 – 3.40).The overall mean duration of

Yes

38

33

0.66 (1.72 – 4.29)

No

2.0

exclusive breast feeding among respondents was 3.82

No

response

17

13

0.69 (0.65 – 3.35)

months (with 95% confidence interval 3.25 – 4.39).

6

5

0.003

348

Discussion

encourage mothers to practice EBF of subsequent babies

while negative experiences would do the opposite.

The

survival analysis method was used to analyze data

Again, personal motivation might influence even a

from 112 mothers. The median duration of EBF in the

mother who had unpleasant experiences the first time to

current study (three months) was lower than five months

attempt EBF the next time around. The extent to which

reported by Chudasamaa et al among 498 mothers in-

14

previous experiences and motivation play a role in EBF

fant pairs in South Gujarat region of India, five years

will therefore differ from one cohort of mothers to an-

ago. On the contrary, the median duration of EBF re-

other.

ported in the current study is similar to three months

reported by Setegnet al

15

among 608 mothers in Goba

In

the present study, prenatal EBF plan by way of prena-

district, Southeast Ethiopia. However, it is of interest to

tal feeding advice was found to be associated with

note that the median duration of EBF reported in the

longer duration of EBF. This finding was in agreement

present study was higher than the reported national dura-

with a study conducted among mothers in Bahir Dar

City, Northwest Ethiopia . This might be attributable to

21

tion of half a month but less than seven months reported

in

Southwest Nigeria by the National Population Com-

planning, increased preparedness, and commitment to

mission .

16

achieve EBF. Similarly, the postnatal feeding advice

was associated with longer duration of EBF.

It

was observed in the present study that the month dur-

ing

which the highest number of mothers discontinued

EBF

was at the end of first month. The explanation for

this

finding might be the effect of work resumption.

Conclusion

Usually working mothers in Nigeria are allowed 12

weeks of maternity leave which equals approximately

In

conclusion, this study identified birth order, prenatal

three months. Under these circumstances, mothers are

feeding advice, and postnatal feeding to be associated

prompted to resort to the supplementation of infant for-

with exclusive breastfeeding and that practice of exclu-

mula before three months so that their infants get accus-

sive breast feeding among mothers declined to below

tomed to bottle feeding. Maternal fatigue and the diffi-

20% by the end of four months when they may have

culty in juggling the demands of work and breastfeeding

resumed work. Health workers in private health facilities

may also contribute to this issue. The finding indicates

should play a more prominent role in providing informa-

that the passing and enforcement of legislation that sup-

tion about exclusive breastfeeding to mothers before and

ports working mothers who want to breast-feed exclu-

after delivery.

sively should be a priority. Such legislation includes

initiating breastfeeding-friendly work environments, as

Authors’ contributions

well as the extension of maternity leave to encourage

Akodu SO: Conception, Data collection, Analysis,

mothers to exclusively breastfeed their babies to im-

Manuscript writing.

prove child health outcomes.

Njokanma OF: Conception, Data collection, analysis

Disu EA: Conception

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) experiences of two

Anga AL: Conception, Data collection

groups of infants namely, those of first birth order and

Kehinde OA: Conception, Data collection

those of second or higher birth order were determined.

Conflict of interest: None

The median duration of EBF was observed to be signifi-

Funding: None

cantly higher among infants with second or more order.

This observation might be related to previous breast

feeding experiences of their mothers. The effect of

mother parity on duration of EBF is still a matter of con-

troversy. While some authors have reported that lower

Acknowledgement

parity is associated with longer duration EBF others

17

have documented that higher parity leads to longer dura-

We

thank all the mothers who participated in the study

.

In another study , it was asserted that

20

tion of EBF

18,

19

as

well as the Medical Director and staff of Isalu

parity had no significant influence on duration of EBF.

Hospitals Limited, Ogba, Lagos.

It

would appear that positive personal experiences would

References

1.

WHO. Indicators for Accessing

2.

Agbo HA, Envuladu EA, Adams

3.

Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE,

Breastfeeding Practices. WHO/

HS,

et al. Barriers and facilitators

Bhutta ZA, Morris SS. The Bella-

CDD/ SER/911. Geneva: World

to

the practice of exclusiveBreast

gio

Child Survival Study - How

Health Organization 1991.

feeding among working class

many child deaths can we prevent

mothers: A studyof female resident

this year? Lancet

2003; 362:

65 –

doctors

in tertiary health institu-

71.

tionsin Plateau State. J

Med Res

4.

Jelliffe DB, Jelliffe EF. Human

2013; 2: 112 – 6.

milk in the modern world. New

York: Oxford University Press

1978.

349

5.

Quigley MA, Kelly YJ, Sacker A.

11.

Shirima R, Greiner T, Kylberg E,

17.

Sloan S, Sneddon H, Stewart M,

Breastfeeding and hospitalization

et

al. Exclusive breastfeeding is

Iwaniec D. “Breast is best? Rea-

for

diarrheal and respiratory infec-

rarely

practised in rural and urban

sons why mothers decide to

tion in the United Kingdom Mil-

Morogoro. Tanzania Public Health

breastfeed or bottlefeed their ba-

lennium Cohort Study. Pediatrics

Nutrition 2000; 4(2): 147-54.

bies and factors influencing the

2007; 119: 837 - 42.

12.

Oyedeji GA. Socio-economic and

duration of breastfeeding,”Child

6.

Victora CG, Smith PG, Vaughan

cultural background of hospital-

Care Pract 2006; 12: 283 – 97 ,

JP,

et al. Evidence for protection

ized children in Ilesha. Nig J

Pae-

18.

Wojcicki JM, “Maternal prepreg-

by

breast-feeding against infant

diatr 1985; 12: 111 - 7.

nancy body mass index and initia-

deaths from infectious diseases in

13.

Allison PD. Survival analysis

tion and duration of breastfeeding:

Brazil. Lancet

1987; 2:

319 –

22.

using SAS: A practical guide.

a

review of the literature,”J

2

ed. Carry: SAS Institute Inc;

nd

7.

Popkin BM, Adiar L, Akin J,

Women Health 2011; 20: 341 – 7.

Black R, Briscoe J, Fleiger W.

2010.

19.

Abada TSJ, Trovato F, Lalu N.

Breast feeding and diarrheal mor-

14.

Chudasamaa RK, Patelb PC, Kav-

“Determinants

of breastfeeding in

bidity. Pediatrics

1990; 86:

874 –

ishwarc

AB. Determinants of Ex-

the

Philippines: a survival analy-

9.

clusive Breastfeeding in South

sis,”SocSci

Med 2001;

52: 71

–

8.

Arifeen S, Black RE, Antelman G,

Gujarat Region of India. J

Clin

81,

et

al. Exclusive Breastfeeding

Med Res 2009;1:102-8

20.

Ekstrom A, Widstrom A, Nissen

Reduces Acute Respiratory Infec-

15.

SetegnT, Belachew T, Gerbaba M,

E.

“Duration of breastfeeding in

tion and Diarrhea Deaths Among

Deribe K, Deribew A, Biadgilign

Swedish primiparousandmultipa-

Infants in Dhaka Slums. Pediatrics

S.

Factors associated with exclu-

rous women,”J

Hum Lact

2003;

2001; 08; e67. Available from:

sive breastfeeding practices among

19: 172–8.

http://www.pediatricsdigest.mobi/

mothers in Goba district, south

21.

Seid AM, Yesuf ME, Koye DN.:

content/108/4/e67.full.pdf+html

east Ethiopia: a cross-sectional

Prevalence of Exclusive Breast-

9.

Ssenyonga R, Muwonge R, Nan-

study. Int

Breastfeed J

2012; 7:17

feeding Practices and associated

kya

I. Towards a Better Under-

- 25

factors among mothers in Bahir

standing of Exclusive Breastfeed-

16.

National Population Commission

Dar

city, Northwest Ethiopia: a

ing

in the Era of HIV/AIDS: A

(NPC) Nigeria and ICF Macro:

community based cross-sectional

Study of Prevalence and Factors

Nigeria Demographic and Health

study. Int

Breastfeed J

2013; 8:14

Associated with Exclusive Breast-

Survey 2008 Calverton, Maryland,

- 22.

feeding from Birth, in Rakai,

USA:NPC and ICF Macro

Uganda .

J Trop

Pediatr 2004;

50

2009.Available from: http://

(6): 348 - 53.

www.population.gov.ng/images/

10.

Haider J, Kloos H, Haile Mariam

Nigeria%20DHS%202008%

D,

et al. Food and Nutrition. In:

20Final%20Report.pdf.

Berhane Y, Haile Mariam D,

Kloos H, Eds. The Epidemiology

and

Ecology of Health and Dis-

eases in Ethiopia Addis Ababa,

Ethiopia: Shama Books 2006.